From October 21st to 29th, 2023, five artists from the Asterisk* art collective exhibited their work at the Dutch Design Week festival in Eindhoven as a part of the ArtEZ x DCFA Community Research Programme. The art collective was originally formed in 2022 to push the boundaries of education and research by giving the artists time and space for critical thought, reflection, rephrasing, and contributive critique.

During this summer programme, which was based in Pakhuis de Zwijger’s satellite community centre New Metropolis Nieuw-West, Designing Cities for All partnered up with ArtEZ and Asterisk* to explore regeneration in Amsterdam Nieuw-West and delve into the relationship with their surroundings and the rapid urban development in the area. As part of their research, they collected residents’ stories, which turned out to often revolve around experiences of collective trauma and personal displacement. This led the artists to redefine regeneration as a process of collective healing. The Dutch Design Week exhibition showed the results of this process.

Join DCFA intern Yuka on a tour of the exhibition below!

Heavy rain pouring outside, the calmness of the spacious grey exhibition hall feels welcoming. While my boots squeak on the floor with each step, my ears also catch a soothing melody and muffled voices at a distance. There is a little bit of heaviness in the air, carrying the memories and stories. Where shall I start?

Art as healing

Following the calming sounds, the first work of art I see is Viktoria Kova’s project The LAND of GOOD, curated by Natalia Sudova. While interacting with the locals in Nieuw-West, curator Natalia sought practical ways to address their traumas through the incorporation of the specific artistic practice of transformative art. This resulted in the projection of a moving iris with meditative sounds. This visual and audio artwork is designed to provide self-healing experiences by using specific colours, sounds, and vibrations. Comfortably laying on a bean bag, my eyes are caught by the mystical eye on the screen. It almost feels like the slowly rotating iris is seeing right through me. Yet, this experience is not intimidating. Rather, the combination of soothing pads and the gradual shift of colours calm me down. Being pulled out of reality, my mind is fully present. Through this piece, I felt the potential of art to regenerate individuals and heal traumas.

Reality and perception

Refreshed, I walk towards the wall at the back of the exhibition. There’re four big pictures and a video by Blise Orr: The city as data and Familiarity and distance. Both Blise’s artworks concern the gap between the changing reality and its perception due to the rapid advancement of technology and urban development. The city as data, a collection of pictures, transforms Nieuw-West’s landscapes into black-and-white rendered architecture. I feel as if I am looking at a video game. But the places portrayed are real. Even a familiar place I knew before seems lifeless in the picture. Modelling has become a common practice in architecture. But how does this gamification of a place affect our understanding of the citizens and non-citizens alike? The video, named Familiarity and distance, offers another perspective on this. The video is based on Blise’s conversation with her Glaswegian grandmother. Her grandmother’s story sheds light on the story of those who live in spaces of revitalisation. Although the story takes place in post-war Glasgow, Scotland, the longing for the feeling of home and familiarity she expresses is universal. Looking at birds-eye pictures of Amsterdam Nieuw-West next to the video, I couldn’t stop mirroring her experiences to those of the inhabitants of Nieuw-West.

Transgenerational trauma

In contrast to Blise’s monotone style, the installation by Yonah de Beer (INSI Art) is full of colours. Each portrait is framed with yellow, dark green and radish red. Despite the popping aesthetics of the artwork, Mijn Stamboom Huilt reveals transgenerational trauma in Yonah’s own family through combinations of a video, a poem and portraits. While the different symbols around the portraits speak of the individual experiences of family members, the circularity of the artwork reminds me of the underlying traumas that are passed on from generation to generation and affect each member’s life. At the centre of the installation, the video is slowly projecting Yonah’s childhood memories shot by shot. Listening to Yonah’s voice letter to his younger self, I, too, started recollecting my memories back in the day. Facing our own traumas is not an easy process and discussing them in the public space is regarded as taboo. Yet, Yonah’s artwork proves that traumas can connect us. It empowers me to break the taboo and gives me hope for psychological regeneration as a society.

Re-envisioning place

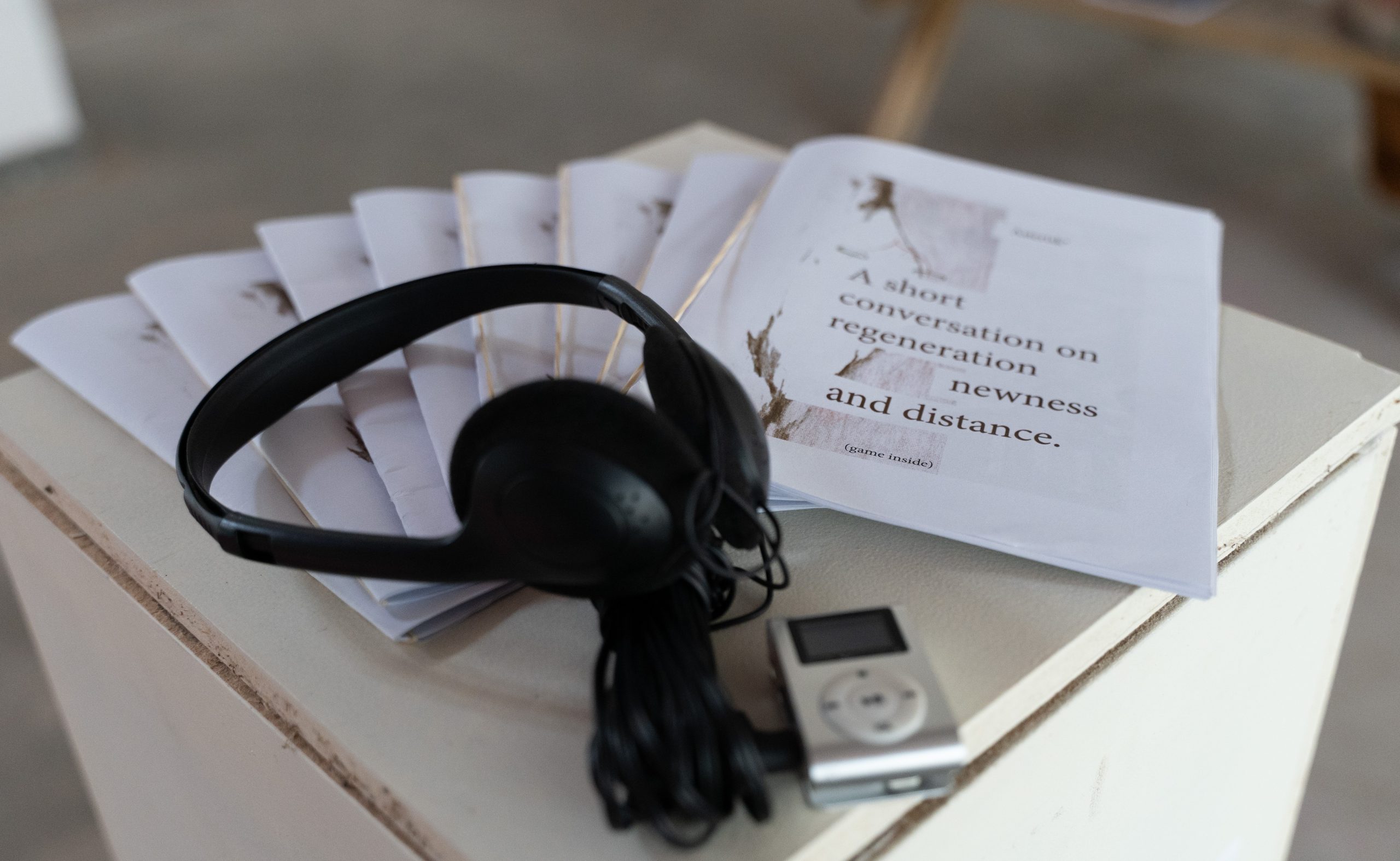

The current exhibition is not just about visual and audio works, but also a game. Guided by the audio instruction, I play the game Site-specific feeling developed by Aditi’s. The game is structured around our six senses. It invites us to move around in space and make observations. Taste, sound, vision, touch, smell… my senses open up and I pay more attention to what is around me. The dripping rain echoed around the concrete room. The exposed ceiling amplifies the coldness of the autumn air. Moving around the hall, the audio-guide continues to the questions of how we envision the space based on our memories and imaginations. Bright lights coming in, people interacting with themselves and others through the artworks… For Aditi, regeneration is healing. During the fast-moving regeneration process in the neighbourhood, we tend to forget to ask ourselves how we want the space and the community to be healed. Aditi’s game is a strong tool for reflecting on what we want to give and receive in space based on our grounded sensory experiences.

Natural vs. Artificial?

Completing the lap, I tune into Malou van der Veld’s two audio-visual works: Dancing in the Dirt and Monster of Sloterplas. Malou’s works delve into the blurring line between nature and man-made by examining two locations, TATA Steel and Sloterplas. Dancing in the Dirt shows three interviews to unfold different narratives of TATA Steel, an industrial complex in IJmuiden that is accused of releasing heavy metals and extensive energy misuse. While listening to her interviews with stakeholders of TATA Steel, the vast industrial complex on the screen suddenly transforms into a wildlife sanctuary. This shift is also happening in the artificial lake in Amsterdam Nieuw-West, Sloterplas. The eerie soundscape of Monster of Sloterplas flows through my body. Malou has beautifully woven together local myths and 1950s archival material, calling attention to the paradoxical situation where the artificial lake has become the refuge for non-human beings. Malou’s soundscape breaks down the dichotomy of nature and man-made environment in my mind and invites me to reconsider what defines a space.

Inside this one exhibition hall, I encountered diverse stories of regeneration as a process of collective healing. Despite the different interpretations and applications of regeneration in each artwork, all of them hinted at the need to challenge the status quo and the potential of art to facilitate a regeneration process. While Malou exposed a false dichotomy of nature and artificiality, Blise highlighted the gap between the fast-changing urban development and the perception of people living within it. Yonah’s journey of reconciliation with his past reminded us of the importance of discussing our past. Aditi provided a playful tool to reimagine present spaces and Natalia’s curated art vividly demonstrated how regeneration process would feel.

Each artist connected with regeneration in their own way. Now what is my take on regeneration?